Introduction

Logistics and shipping can prove complex even for non-polar AUV campaigns. The contractual and legal aspects, especially if operating in foreign waters, suggest that specialist professional advice should be sought at the earliest possible stage. For example, for over a decade the UK National Oceanography Centre has engaged a logistics and shipping specialist company where one of their staff spends time at the Centre to be fully aware of the Centre's needs and to be available to staff to provide immediate advice.

Considerations at the design or procurement stage

AUV designers, owners and operators should really consider logistics and shipping at the very earliest possible stages. While most of the following are not specific to polar AUV operations it does no harm to list them here, for instance:

• Might the AUV contain sub-systems that limit the geographical areas the AUV may be used, or prohibit transit through certain countries? For example, might sub-system options being considered at the design stage include those that could be subject to the US International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR)? Might items be on the US Munitions List? For example, an AUV operating in polar regions may require a high-specification, low power, advanced integrated navigation system that might be ITAR listed. Might there be a suitable alternative system available that is only subject to the less restrictive US Export Administration Regulations (EAR)? Or might there be a regulation-free product from another country? Another relevant example would be a low frequency passive sonar for marine mammal studies that would seek to discriminate between animal and other sounds (e.g. shifting sea-ice, mn-made sounds). Such sensors and the processing and analysis software from the US may well fall within the scope of ITAR or EAR.

• How might choices available at the specification, design or purchase stage affect the ease or cost of logistics and shipping? For example, at the design stage of a large AUV consideration should perhaps be given to the available diagonal length of about 6.3m the length in an ISO standard 20' container. Or the size and weight restrictions for a Twin Otter aircraft might be important, either for a complete vehicle or for the modules of a larger vehicle. The ISE Theseus vehicle was designed and built in six sections to suit the hatch dimensions of a Tein Otter.

For a large AUV launch and recovery system, might it be designed to fit within a 20' ( if need be, an open top) container? Otherwise, might it need a High Cube container or might it need to be over-size and thus restricted to being carried as the uppermost load on a ship and therefore at a premium price?

• Might the choice of energy storage or generation system cause difficulties with logistics or shipping? If the AUV comes with a semi-fuel cell, for example, or, in the future, a fuel cell, are there logistics limitations for the polar regions that would preclude its use due to the need to supply, store, and dispose of, or retrieve, the reactants?

• Are there any complications arising from how the AUV was purchased? Some operators may have their vehicles within a Customs Warehouse, where import duty, Value Added Tax or other taxes may be suspended. The conditions of a Customs Warehouse may place conditions on where the vehicle may actually be used (e.g. they may not be used within the Territorial Waters of the state or a Customs Union to which it belongs).

Considerations at the time of campaign planning

While different countries, different groups (universities, research centres, companies, the military) will vary in the detail of the processes they need to follow to plan for and organise the logistics and shipping for polar AUV campaigns there will be several points in common:

• Is the campaign to be ship-based, at an ice-camp or a hybrid?

If ship-based, and on an ocean-going vessel, then vessel operators will have well-proven processes to put the required logistics and shipping in place. For the research community supported by NERC (UK), NIOZ (Netherlands), GEOMAR (Germany) and CSIC (Spain) there is a single web portal for users to apply to use marine and associated facilities. Past, current and future programmes from these agencies can be studied, and the deployments of AUVs and gliders checked. Other nations may have equivalents. Registered users can check on available equipment, upload their plans, and, when approved, check on the progress with logistics and shipping.

If the operations are from an ice-camp see the relevant section on the Ice Camp page.

• The length of time needed to ship to and from the operations area may well be (much) longer than for campaigns in temperate regions. If sea freight is required, it will rarely be to the final destination, trans-shipment may be needed, and the final leg may well be on the deployment vessel. For example, equipment may be sent by commercial sea freight to Punt Arenas, Chile to be picked up by the deploying vessel for operations either side of the Antarctic Peninsula. Logistics and specialists should always be consulted, they should find out the important details, for example if the trans-shipment port has cranes suitable for the loads required, as well as eto provide estimates the total time and the loading deadline.

• Seek advice on whether you may use an ATA Carnet to assist the customs process of taking your AUV etc. out of the country temporarily. If you cannot use a Carnet, a Duplicate List may be applicable. You need to be fully aware of what reporting requirements will be if you lose the AUV and therefore cannot reimport.

• Be sure that your AUV, its internal modules and all ancillary equipment being shipped by commercial freight can stand the rigours of possible mishandling, vibration, extremes of temperature that may be encountered. An AUV for polar operations may include modules with requirements to always be within a certain temperature range, e.g. not above X˚C for batteries, or not below Y˚C for, say, the liquid reagents in a wet-chemical sensor. Specific supply chain temperature loggers, and vibration and shock loggers are readily available. Incidents do occur: a large AUV suffered damage to its battery pressure vessel when vibration on a transatlantic freighter caused the insulation around individual cells to fail, resulting in short circuits not protected by fuses, leading to excessive heat, gas build up and caustic electrolyte leakage that etched the glass fibre pressure vessel.

Logistics and Shipping

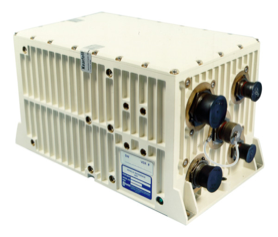

The Kearfott T24 Inertial Navigation System is a high-specification sub-system for AUV navigation in the absence of GPS or acoustic positioning. The company announced in March 2019 that the T24 was no longer subject to US ITAR and could be supplied under the Export Administration Regulations. Image from Kearfott.

Example of an AUV launch and recovery system that has taken heed of good logistics and shipping practice. The entire Hugin system is built into a standard ISO shipping container. Image from Kongsberg Maritime.

Several polar AUV expeditions have been supported by Twin Otter aircraft. Able to operate with wheels, floats, skis, wheel skis or tundra tyres, with a typical maximum payload of 3500 lb and a 56" x 50" cargo door this is a versatile aircraft. The ISE Theseus AUV was designed in six sections to fit a Twin Otter's cargo door. The pictured aircraft if from Kenn Borek Air, a Calgary-based operator with extensive polar experience. Image from Kenn Borek Air.