Introduction

AUV operations from ice camps can span a large range of logistics requirements.

At the low logistics end, an ice camp might only be needed for some hours, for example to support a single-person portable AUV such as the 4kg ecoSUB deployed at an ice-covered lake, or into a coastal polynya, or at a seal breathing hole. All that might be needed were two people, a tent and survival equipment and provisions on a sled.

In the most complex ice camps AUV operations may be just one activity. If situated 100s of km out in the Arctic ocean, setting up the camp may involve initial personnel flown in via an aircraft such as a Twin Otter, perhaps larger items via paradrops from C130 aircraft, or perhaps equipment and resupply visits from icebreakers, or, in some cases, an icebreaker may remain drifting with the ice camp.

Operations from Ice Camps

Types of Ice Camp

The US Antarctic Program (USAP) has three indicative levels of field camps, a designation that would also be applicable to the Arctic:

• Major Camps - Typically multidisciplinary and multi-project but clearly with a common location, accommodation would likely be in Jamesway wood/canvas huts. These are of fixed height and width but the length can vary. An example of a major camp to support AUV operations was in place off Borden Island, Nunavut in 2010 to support the NRCan ISE Explorer AUV. Comprising at least 13 huts, it was built on fast multiyear ice.

Logistic support for a major camp would typically be by helicopter and or Twin Otter aircraft depending on range from a base.

Given the logistics and resource requirements major camps are likely to be national or international coordinated efforts where an AUV project would be a component part. The AUV group would have a logistics contact point and most of the organisation would be done by specialists. In essence the process could parallel an AUV group's participation on a large research ship or icebreaker with a multidisciplinary party.

Extensive, insightful and open details on AUV operations from a large ice camp, and from subsidiary sites along a 180km transect, are given by Bruce Butler in his book, "Into the Labyrinth: The making of a modern-day Theseus". His picture galleries of transportation around the ice camps, and of living and working on the Arctic ice provide insights not usually gleaned from published reports or papers.

• Huts - Huts may be erected for a particular project for one season or with the intention to stay in place for several years. Huts have been used, for example, on the fast ice in McMurdo Sound, on the ice-covered Lake Bonney, Taylor Dry Valley, Antarctica and in the Arctic on drifting multiyear ice floes.

A Hut may be purpose-designed to support AUV operations. For example, for the Stone Aerospace Endurance AUV operations at Bloody Falls, Lake Bonney in 2008 the floor of the large hut included a 'cut-out' over the hole in the ice-covered lake through which the AUV would be deployed and recovered. This substantial hut was built on a frame of 8"x8" beams, with each of the 500lb floor panels anchored to the ice. An All-Terrain Vehicle (ATV) helped the team move the heavy items from where the helicopter had left them. In this case the AUV team were a short distance from a permanent Jamesway camp at Lake Bonney with a kitchen, community space and WiFi.

The 'Huts' category may also include large tent-like structures such as the 'Polar' range from Weatherhaven. Two of their half-dome structures were used to form a 6.5m by 16m tent for the NRCan ISE Explorer AUV near Borden Island in 2010.

• Tents - Doble and other have described what they consider to be the "minimal logistical requirements for a through-ice AUV operation" at a tent camp. In this instance, their camp was on sea ice just north of the Canadian Forces Station at Alert on Ellesmere Island, Nunavut. They considered that the tent camp was "pared to the minimum required to work in safety and comfort". The camp consisted of a Weatherhaven 12' x 20' heated working tent for the AUV, covering the 3m x 1m ice hole, a three-person sleeping tent and a separate small toilet tent. The working tent doubled up as the cooking tent, and, like the sleeping tent, was heated with drip-feed kerosene stoves. The camp was pitched for just one week, set by the constraints of the Alert base and Twin Otter aircraft support. The main method of deployment from shore for the camp infrastructure was by skidoo. While the number of skidoo trips is not known, they considered that, if the Twin Otter could have landed safely, it would have taken three full loads to deploy this minimal tent camp.

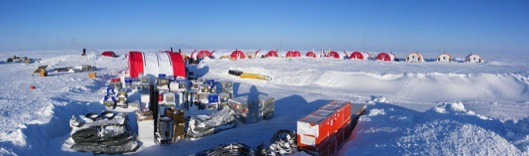

The major ice camp for some 40 people off uninhabited Borden Island, Nunavut, for the 2010 NRCan Explorer AUV Cornerstone project. Located some 600km northwest of Resolute, the camp was also the base for four survey helicopters. Two runways were cleared for Twin Otter, DC-3 and DHC-5 Buffalo aircraft. Image from DRDC Atlantic.

Laying the wooden base for the Stone Aerospace Endurance AUV camp at Bloody Falls, Lake Bonney, Antarctica in November 2008. Note how floor sections are anchored to the ice, and the cut-out for AUV deployment through the ice. Image from Stone Aerospace field notes.

A minimal tent camp for AUV operations as described by Doble and others. Their 2008 camp on fast ice north of Alert, Ellesmere Island, Nunavut, comprised a Weatherhaven tunnel tent (right), a small toilet tent, centre, and a three-person sleeping tent (left). Image from Doble and others (2008).

Ice Camp Support and Logistics

For scientific researchers, where their nation has a clear lead organisation for polar research, such as the British Antarctic Survey in the UK, Norwegian Polar Institute in Norway or the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany, these organisations should be able to provide advice on the support and logistics requirements for ice camps. In other countries, such as the United States, a national funding agency may provide advice and guidance on independent providers of ice camp services.

National Centre example - the Norwegian Polar Institute

For example, the Norwegian Polar Institute (NPI) can provide the following services in support of ice camps:

• Leasing of field equipment, with a detailed inventory and pricing schedule available online. The list is extensive, and includes tent-based camp equipment, personal clothing, medical and emergency equipment, communications, boating, generators and so on.

• Training in polar safety, including rifle training for the Arctic.

• Transport facilities.

• Daily communications check-in for parties working remotely in the Svalbard region (at 1900UTC). This check is compulsory for NPI parties and offered at no charge for others renting their communications equipment from NPI. The default method is Satellite Phone, but can be by VHF by prior arrangement and if the separation distance allows.

In addition, specifically for the Antarctic, and related to ice camps, the NPI can offer groups construction services, including lease of construction machinery and personnel in most technical construction trades, and workshop and technical assistance.

Advice and Guidance example - the United States National Science Foundation

Within the National Science Foundation's Office of Polar Programs (OPP) the Arctic Research Support and Logistics (RSL) programme supports fieldwork of those projects funded by the NSF's Arctic Sciences Section. RSL may also support or co-fund other projects funded by NSF or other agencies. The requirements are complex, and the RSL web pages (and probably RSL staff) should be consulted well in advance of a proposal being submitted.

Currently CH2MHILL Polar Services holds the prime contract from RSL to support Arctic research parties. The list of services is similar to that of the NPI above, but also includes coordination with local communities and access (for a fee) to research hubs in Alaska and Greenland.

Guidance on communications and information assurance services is provided to RSL by the Space and Naval Warfare Systems Command (SPAWAR). SPAWAR have a list of Arctic IT providers, can conduct site visits, and, certainly in the past, have issued Newsletters on communications and information security for US Arctic research programmes.

The Field Manual for the US Antarctic Program is a treasure trove of practical advice on field operations.

Insulated shelters on ski-equipped bases supporting AUV operations during the ANZFLUX experiment on sea ice over the Maud Rise in the northern Weddell Sea in 1994. These shelters were constructed aboard the RV Nathaniel B. Palmer and moved into position by snowmobile. In addition to AUV deployments, these shelters housed the surface units for wire-deployed instruments including turbulence probes, Acoustic Dopper Current Profilers, a free-fall microstructure profiler as well as instruments for atmospheric measurements. Photograph by P. Guest.

The ice camp for the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution REMUS AUV expedition to the fast ice off Barrow Alaska in 2010. This was the second tent camp constructed by the team, the first having been damaged by a passing iceberg. Local Inupiat were employed to support the ice camp, to provide protection against polar bears and to transport the equipment to and from the site using sleds pulled by snowmobiles. Image from WHOI (photo 13 by Amy Kukulya).