Introduction and Status

Caveat: These sections on Legal Issues have been compiled by a generalist in AUV operations and technology. The law concerning AUVs and their operations remains complex with a number of uncertainties and no clear international harmonisation. Operators are advised to seek their own legal advice from qualified legal experts, advice specific to their own country and area of operation.

This Guide does help in prompting some of the questions to ask when seeking advice.

Key sources of legal opinions on the operation of AUVs

The Volumes Two and Three from 'The Operation of Autonomous Underwater Vehicles Series' written by academic and practicing lawyers Prof E D Brown and Prof N J J Gaskell, published by the Society for Underwater Technology in 2000, remain key source documents on the subject. Volume Two is a highly detailed and nuanced assessment of the legal matters with extensive footnotes on possible legal precedents. Volume Three is the more practical document, answering a set of questions such as would be posed by an operator. We have drawn extensively from Volume Three to provide specific answers to questions on Antarctic Operations.

Showalter, a lawyer at the National Sea Grant Law Center, University of Mississippi, wrote a succinct, 3-page, conference paper on "The law governing autonomous undersea vehicles: what an operator needs to know" in 2003, emphasising Collision Regulations and Lights, while touching on liability and salvage.

Henderson, a US Navy Judge Advocate General Corps lawyer, writing in the Naval Law Review in 2006 titled his paper "Murky Waters: The legal status of unmanned Undersea Vehicles". Four years later another US Navy lawyer, Kraksa, argued that unmanned naval AUVs fitted within existing legal frameworks such as the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. However, for others, there remain many unanswered questions on the legal issues surrounding AUV operations, including the fundamental question of whether an AUV is a 'ship'. Giunta's (2015) paper with its title "The enigmatic juridical regime of unmanned maritime systems" illustrates the continuing uncertainty [juridical: a non human legal entity].

Two chapters in recent books still pose questions rather than offering clear practical guidance. In "Maritime Security and the Law of the Sea" Chadwick's chapter title asks "Is International Law ready?", while, in "Governing Marine Living Resources in the Polar Regions" Leary's chapter title asks if 'Frozen robots' are "A new tool or a new challenge for sustainable ocean governance?".

Other sources

Rogers (2012) provides a broad review by a knowledgeable non-lawyer of the breadth and scope of the legal regime relating to AUVs, covering research, commercial and military vehicles. He points out that some countries consider 'underwater vehicles' to include AUVs in Article 20 of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which reads, "Submarines and other underwater vehicles - In the territorial sea, submarines and other underwater vehicles are required to navigate on the surface and to show their flag" - this requirement would apply to underwater vehicles of states other than the particular coastal state. In his opinion

The International Maritime Organisation's International Code for Ships Operating in Polar Waters (the Polar Code) would apply if a ship-based AUV missions, or hybrid ship and ice camp missions were planned.

The Institute of Marine Engineering Science and Technology (IMarEST) has a Special Interest Group on Ocean Governance that has prepared a position statement on the Polar Regions. The Group's membership may be a souce of useful advice.

Arctic and Antarctic: Two contrasting legal regimes

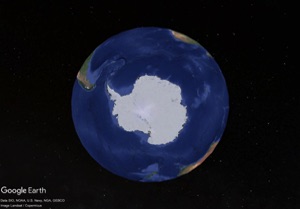

As illustrated in the maps opposite the Arctic and Antarctic have very different legal regimes for maritime operations. In summary, the extensive Exclusive Economic Zones of the five Arctic nations dominate, while there is contention over the claims for extended continental shelf claims. Although the single Antarctic Treaty System sets the regulations south of 60˚S, for an AUV operator, the applicable law would be their own national legislation implementing the Antarctic Treaty. For example, in the UK this would be the Antarctic Act 1994.

Concerning the use of AUV’s to undertake State funded Polar research: In the Antarctic this is controlled by the State's own Government, for example in the case of the UK via the Foreign and Commonwealth Office through the application for, and granting of, a ‘Permit’. In the Arctic if the AUV Marine Scientific Research (MSR) is funded by States other than the Arctic State in whose waters it would take place then formal application is required under Part XIII of UNCLOS. Guidance on how to make an application can be found in the UN Publication ‘Law of the Sea – Marine Scientific Research – A revised guide to the implementation of the relevant provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea'.

Commercial AUV activities: In Rogers' opinion (2020) the use of AUVs to undertake commercial activities such as hydrographic, geophysical and fisheries assessment in the Antarctic area regulated by the Antarctic Treaty is not likely to be approved. Within the Arctic maritime zones under the control of the eight Arctic States (five Arctic Ocean and three high latitude) would require explicit permission from those States unless the commercial use was sponsored by the Arctic State in whose waters the operations would take place. However, in the Arctic, outside of the maritime zones under the control of the Arctic States, commercial AUV activities is allowed as a freedom of the High Seas.

Operations of AUVs for defence purposes: In the Antarctic area regulated by the Antarctic Treaty, "any measures of a military nature" are prohibited (Article 1). However the same Article states that the Treaty, "shall not prevent the use of military personnel or equipment for scientific research or for any other peaceful purpose". In the Arctic maritime zones under the control of the Arctic States the situation is complicated. Most major Maritime Powers would consider the deployment of naval AUVs for peaceful purposes outside the territorial sea of a Coastal State a Freedom of the High Seas. This is an issue that is not specific to the Arctic States, it continues to be a controversial question in international maritime law, with no authoritative judicial ruling to date, Papastavridis (2017).

The Arctic and Antarctic differ so much in their geopolitics affecting the legal issues that each must be dealt with separately.

Legal Issues of AUV Operations in Polar Regions

The Arctic Ocean is surrounded by five countries: Denmark (as Greenland), Canada, the United States, the Russian Federation, and Norway. While there is clarity with the the 200 nautical mile Exclusive Economic Zones the situation in the central Arctic Ocean around the North Pole is complex. Map courtesy IBRU, Durham University, UK who provide full detailed notes.

In contrast, the Antarctic continent and the whole area south of 60˚S including all ice shelves and islands is regulated through the Antarctic Treaty System. While there are several Field Codes of Conduct available, there is no code for AUV operations.

Territorial Sea, Exclusive Economic Zone, High Seas, The Area, what do these names for the maritime zones mean? Check the definitions using this link.